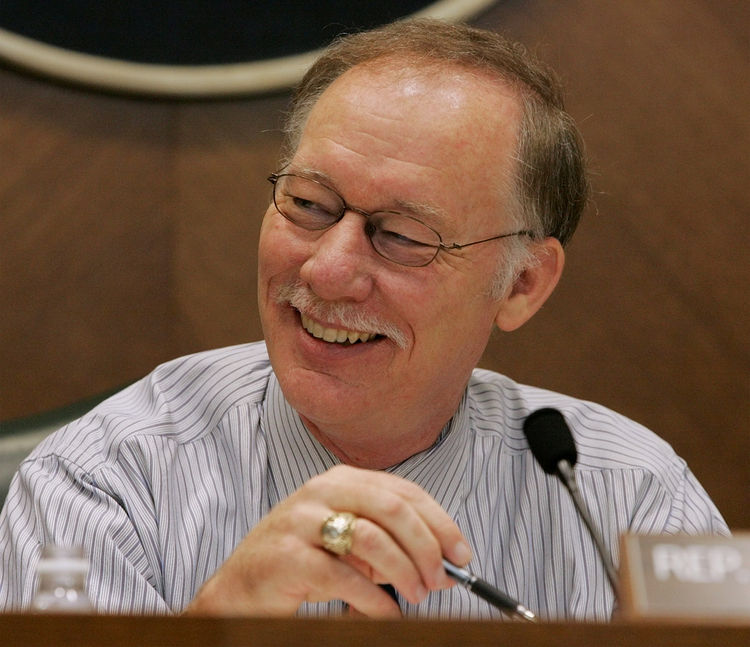

(Bloomberg) — Jim Keffer is Republican state lawmaker in Texas with a permit to carry a concealed weapon and doubts about whether human activity is causing global warming.

Cisco DeVries is the former aide to the mayor of Berkeley, California, whose home has solar panels on the roof and a Nissan Leaf in the driveway. He calls fighting climate change the defining issue of this generation.

But the Texas recipient of the “champion of free enterprise” award and the California self-described “policy entrepreneur” share one thing: They’re both promoting a new financing mechanism that aims to break the partisan deadlock over renewable power and energy efficiency.

“There were some raised eyebrows,” Keffer, chairman of the Texas House’s Natural Resources Committee, said of his authorship of the measure authorizing the funding scheme in Texas. “But it’s a no-brainer. Anything we can do to conserve resources and upgrade our infrastructure is a good idea.”

Keffer and DeVries are united behind the plan, touted by Scientific American as an idea that could change the world, that is spreading to states beyond red Texas and blue California. The Property Assessed Clean Energy, or PACE, lets property owners put the cost of energy upgrades on a property tax bill and pay it off over several years at a low interest rate. The repayment is their responsibility at no cost to other taxpayers and can be passed on if the property is sold.

‘Huge Opportunity’

“Chairman Keffer sees this is as a huge opportunity for economic development and jobs,” said Charlene Heydinger, executive director of Keeping PACE in Texas, a nonprofit group. “Cisco is more on the environmental side. It’s the same goal, different focus.”

Sewers and buried power lines have been paid for with these municipal tax assessments for decades; proponents argue that extending them to include solar panels, efficient water heaters or insulation is a way to conserve power without government rules or subsidies.

“It has no mandates, no subsidies, states’ rights and local control,” said PACE proponent Jeff Tannenbaum, the founder and president of Fir Tree Partners, a New York-based investment firm with $13 billion in assets. “It speaks to the Tea Party platform, as well as the Democratic Party’s program of job creation.”

Housing Agency

One group that hasn’t gotten the message is federal regulators, and they almost killed the idea. In 2010 housing regulators ruled that government-backed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac couldn’t invest in mortgages with homes that have a PACE assessment. With that statement, an idea that was lauded became just another fancy plan run aground in Washington.

In recent months, a new strategy has emerged that Tannenbaum calls its 2.0 version. And, while green California is essentially thumbing its nose at Washington and continuing with these projects for homeowners, PACE is now expanding in Texas, Ohio, Arkansas, Michigan and Florida as a way to fund bigger commercial projects. Its popularity in these Republican-led states has shocked even its pioneer.

“When Texas passed a PACE law, I knew this was not just a crazy Berkeley idea,” said DeVries, 41. “We got support across the political spectrum. Whether or not someone agrees with my position on climate is irrelevant.”

DeVries was working for Berkeley’s mayor in 2006, helping a group of residents use a special assessment to pay for burying electrical lines, when the idea came to him: Why not do the same for rooftop solar panels?

Energy Savings

Under PACE, an owner or a contractor applies to the government office that runs the program to finance their project. A locality would borrow the money or issue debt for a group of projects. The property owner gets the benefit of a government-backed lower rate and longer term, and can pay off the cost with savings from lower heating or electrical bills.

Some bigger projects can have a 20-year payback, almost three times normal commercial terms, said David Gabrielson, executive director of PACE Now, a Pleasantville, New York-based group promoting the concept.

Because repayment is on the tax bill, the lender gets a lien on the property that’s senior to the mortgage, a better guarantee of repayment than a home improvement or commercial loan. They also aren’t wiped out in a foreclosure. And, as a property assessment, it can be transferred to a new owner.

Big Buildings

Once Berkeley started its program, “this thing went viral,” DeVries said. Tannenbaum went to the White House soon after President Barack Obama’s election to discuss steps the U.S. could take to cut dependence on foreign oil and science adviser John Holdren sent him to DeVries’ nascent experiment. Tannenbaum coined the acronym and now helps fund the advocacy group PACE Now.

The White House included $150 million in its 2009 economic stimulus to help local governments set up PACE districts.

Except it hasn’t changed the world — yet.

In July 2010, just as many PACE programs were kicking in, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, said PACE assessments pre-empted mortgages, and created significant risks for lenders and the two government-sponsored entities.

“PACE loans threaten to move existing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgages to a second lien position and increase the risk of loss to the enterprises and, by extension, to taxpayers,” the agency said in reiterating its position in December.

Fannie Mae

That statement had impact because of the size of the government-backed lenders: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac together own or guarantee 59 percent of new mortgages, according to FHFA.

With that warning from FHFA, PACE programs for homeowners ground to a halt in most of the nation.

In California, Governor Jerry Brown was so incensed that he sued to reverse the decision. He lost, but residential financing began to pick up again over the past two years, as two companies with local contracts ramped up their programs.

Commercial owners are big enough that they can contact their lender and get them to sign off a PACE financing, which could be impractical for millions of homeowners.

In Ohio, where Republican Governor John Kasich signed a measure to freeze a renewable-energy mandate last year, $35 million of PACE projects in the Cincinnati area are up for review this year, said Andy Holzhauser, the chief executive of the Greater Cincinnati Energy Alliance.

Kentucky, home to climate-change skeptic and Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, finalized PACE legislation this month.

“Efficiency’s the one energy issue on which even the Friends of Coal and tree-huggers can agree,” Jonathan Miller, a former state Treasurer pushing the PACE program, wrote in the Louisville Courier-Journal.

Texas Governor Rick Perry, who calls the Environmental Protection Agency’s carbon plan a “direct assault” on energy providers, signed the state measure that Keffer, 62, sponsored to greenlight PACE for commercial buildings. The program includes financing for solar rooftops, but also focuses on efficiency upgrades and water conservation, a huge worry in the drought-plagued state. That’s a new twist on the program.

To contact the reporter on this story: Mark Drajem in Washington atmdrajem@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jon Morgan atjmorgan97@bloomberg.net Steve Geimann